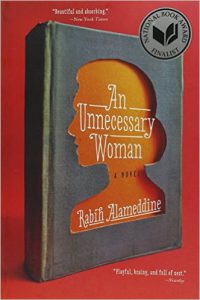

An Unnecessary Woman by Rabih Alameddine

by Rabih Alameddine (Author)

Winner of the California Book Award

Finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award

Finalist for the National Book Award

“Beautiful and absorbing.”—New York Times

An Unnecessary Woman is a breathtaking portrait of one reclusive woman’s late-life crisis, which garnered a wave of rave reviews and love letters to Alameddine’s cranky yet charming septuagenarian protagonist, Aaliya, a character you “can’t help but love” (NPR). Aaliya’s insightful musings on literature, philosophy, and art are invaded by memories of the Lebanese Civil War and her volatile past. As she tries to overcome her aging body and spontaneous emotional upwellings, Aaliya is faced with an unthinkable disaster that threatens to shatter the little life she has left. Here, the gifted Rabih Alameddine has given us a nuanced rendering of one woman’s life in the Middle East and an enduring ode to literature and its power to define who we are.

“A paean to the transformative power of reading, to the intellectual asylum from one’s circumstances found in the life of the mind.”—LA Review of Books

“[The novel] throbs with energy…[Aaliya’s] inventive way with words gives unfailing pleasure, no matter how dark the events she describes, how painful the emotions she reveals.”—Washington Post

Review

Finalist for the National Book Award

Finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award

Washington Post Top 50 Fiction Books of 2014; Kirkus Best Books of 2014; NPR Best Books of 2014; Amazon 100 Best Books of 2014; The Christian Science Monitor Top 10 Fiction Books of 2014

Praise for AN UNNECESSARY WOMAN

“An Unnecessary Woman is a meditation on, among other things, aging, politics, literature, loneliness, grief and resilience. If there are flaws to this beautiful and absorbing novel, they are not readily apparent.”—New York Times

“[I]rresistible… [the author] offers winningly unrestricted access to the thoughts of his affectionate, urbane, vulnerable and fractiously opinionated heroine. Aaliya says that when she reads, she tries to ‘let the wall crumble just a bit, the barricade that separates me from the book.’ Mr. Alameddine’s portrayal of a life devoted to the intellect is so candid and human that, for a time, readers can forget that any such barrier exists.”—Wall Street Journal

“Alameddine…has conjured a beguiling narrator in his engaging novel, a woman who is, like her city, hard to read, hard to take, hard to know and, ultimately, passionately complex.”—San Francisco Chronicle

“[An] opaque self-portrait of an utterly beguiling misanthrope… Aaliya notes that: “Reading a fine book for the first time is as sumptuous as the first sip of orange juice that breaks the fast in Ramadan.” You don’t have to fast first (in fact it helps to have gorged on the books that Aaliya translates and adores) in order to savor Alameddine’s succulent fiction.”— Steven G. Kellman, The Boston Globe

“You can’t help but love this character.”—Arun Rath, NPR’s All Things Considered

“A restlessly intelligent novel built around an unforgettable character…a novel full of elegant, poetic sentences.”—Minneapolis Star Tribune

“I can’t remember the last time I was so gripped simply by a novel’s voice. Alameddine makes it clear that a sheltered life is not necessarily a shuttered one. Aaliya is thoughtful, she’s complex, she’s humorous and critical.”—NPR.com

“[A] powerful intellectual portrait of a reader who is misread….a meditation on being and literature, written by someone with a passionate love of language and the power of words to compose interior worlds. It’s about how, and by what means, we survive. About how, in the end, what is hollow and unneeded becomes full, essential and enduring.”—Earl Pike, Cleveland Plain Dealer

“Beautiful writing…sharp, smart and often sardonic…an homage to literature.”— Fran Hawthorne, The National

“Reading An Unnecessary Woman is about listening to a voice — Aaliya’s — not cantering through a plot, although powerful events do occur, both in the present and in memory…a fun, and often funny, book…rich in quirky metaphors… An Unnecessary Woman is not a game, though; it is a grave, powerful book. It is the hour-by-hour study of a woman who is struggling for dignity with every breath…The meaning of human dignity is perhaps the great theme of literature, and Alameddine takes it on in every page of this extraordinary book.”— Washington Independent Review of Books

“Playful, brainy and full of zest, An Unnecessary Woman is an antidote to literary blandness.”—Newsday

“Aaliya is a formidable character… When An Unnecessary Woman offers her what she regards as the corniest of conceits – a redemption arc – it’s a delight to see her take it.”—Yvonne Zipp, The Christian Science Monitor

“An Unnecessary Woman is a book lover’s book. If you’ve ever felt not at home in the world—or in your own skin—or preferred the company of a good book to that of an actual person, this book will welcome you with open arms and tell you that you’re not alone. You just might find a home within its pages.”— Julie Hakim Azzam, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“An intimate, melancholy and superb tour de force…Alameddine’s storytelling is rich with a bookish humor that’s accessible without being condescending. A gemlike and surprisingly lively study of an interior life.”—Kirkus(starred review)

“Studded with quotations and succinct observations, this remarkable novel by Alameddine is a paean to fiction, poetry, and female friendship. Dip into it, make a reading list from it, or simply bask in its sharp, smart prose.”— Michele Leber, Booklist (starred review)

“Alameddine’s most glorious passages are those that simply relate Aalyia’s thoughts, which read like tiny, wonderful essays. A central concern of the book is the nature of the desire of artistic creators for their work to matter, which the author treats with philosophical suspicion. In the end, Aalyia’s epiphany is joyful and freeing.”—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Acclaimed author Alameddine (The Hakawati) here relates the internal struggles of a solitary, elderly woman with a passion for books…Aaliya’s life may seem like a burden or even “unnecessary” to others since she is divorced and childless, but her humor and passion for literature bring tremendous richness to her day-to-day life—and to the reader’s… Though set in the Middle East, this book is refreshingly free of today’s geopolitical hot-button issues. A delightful story for true bibliophiles, full of humanity and compassion.”—Library Journal

“Around and about the central narrative, like tributaries, flow stories of those people Aaliyah has known…The city of Beirut itself is a character, collapsing, reshaping, renewing, mod¬ern¬ising as Aaliyah herself grows old. Aaliyah’s mordant wit is lit by Alameddine’s exquisite turns of phrase… An Unnecessary Woman is a story of innumerable things. It is a tale of blue hair and the war of attrition that comes with age, of loneliness and grief, most of all of resilience, of the courage it takes to survive, stay sane and continue to see beauty. Read it once, read it twice, read other books for a decade or so, and then pick it up and read it anew. This one’s a keeper.”— Aminatta Forna, The Independent (UK)

“[W]hat Alameddine offers here, most of all, is a window into the lives of Beiruti women… Aaliya, literary devotee, may consider herself “unnecessary”–but the novel proves very necessary indeed.”—Lambda

“A novel that manages to be both quiet and voluptuous, driven by a madcap intimacy that thoroughly resists all things ‘cute’ or ‘exotic.’”—Dwyer Murphy, Guernica

“Beautiful …despite [Aaliya’s] constant claims that she is unlovable it takes only a few pages of reading to realize this isn’t true – she’s extraordinary, even beguiling. She’s tough, opinionated, and deeply caring, but also passive, insecure, and fearful. Complex, in other words, and real. The novel is both intimate and expansive, opening out into the world of politics and war even as it’s rooted in the thoughts of this unnecessary, fascinating person.”— Aruna D’Souza, Riffle.com

“Aaliya is intelligent, acerbic and funny, one of those rare characters who becomes more real to readers than the people around them, and will remain will them for a long time.”—The Daily Star (Lebanon)

“Aaliya’s reminiscences make up “her total globe, her entire world”. In her, we see that feminism resists categorisation and is not defined by the West. Aaliyah embodies the self-determination of both the feminist and the writer, and exhibits vulnerability, determination and wisdom. But, most important, it is in the honesty of Aaliyah’s narration that we see the passion of the modern woman, full of knowledge and a vibrant interior world.”—Sarah Dempster, The Australian

“At once a sublime encomium to the art of reading well, where the pleasures of the text are called to the task of self-making, the novel is also a gentle appeal against loftiness. For every canonical seduction, there is pause for the folly of disconnection, the vanity of denial. In Alameddine’s examination of memory, translation and freedom, there is an insistence that life is more than the cruel absurdities of a reductive reality. An Unnecessary Woman charms with expressive cynicism and inadvertent optimism, shining a unique light on the art of storytelling.”—Readings (Australia)

“This impossibly beautiful funny novel is a window into another world. Rabih Alameddine has drawn a fierce and passionate character whose love of life and literature draws the reader into her labyrinthine story. An Unneccessary Woman is for anyone who has an enduring love affair with books, the desire to understand the human condition or a glimpse into the rich and exotic straddling of life that the city of Beirut epitomises.”—The Hoopla.com (Australia)

“An Unnecessary Woman dramatizes a wonderful mind at play. The mind belongs to the protagonist, and it is filled with intelligence, sharpness and strange memories and regrets. But, as in the work of Calvino and Borges, the mind is also that of the writer, the arch-creator. His tone is ironic and knowing; he is fascinated by the relationship between life and books. He is a great phrase-maker and a brilliant writer of sentences. And over all this fiercely original act of creation is the sky of Beirut throwing down a light which is both comic and tragic, alert to its own history and to its mythology, guarding over human frailty and the idea of the written word with love and wit and understanding and a rare sort of wisdom.”—Colm Toibin

“The extraordinary if “unnecessary” woman at the center of this magnificent novel built into my heart a sediment of life lived in reverse, through wisdom, epiphany, and regret. This woman—Aaliya is her name—for all her sly and unassuming modesty, is a stupendous center of consciousness. She understands time, and folly, and is wonderfully comic. She has read everything under the sun (as has her creator, Alameddine), and as a polyglot mind of an old world Beirut, she reminds us that storehouses of culture, of literature, of memory, are very fragile things indeed. They exist, shimmering, as chimeras, in the mind of Aaliya, who I am so happy to feel I now know. Her particularity, both tragic and lightly clever, might just stay with me forever.”—Rachel Kushner

“There are many ways to break someone’s heart, but Rabih Alameddine is one rare writer who not only breaks our hearts but gives every broken piece a new life. With both tender care and surgical exactness, An Unnecessary Woman leads us away from the commonplace and the mundane to enter a world made of love for words, wisdom, and memories. No words can express my gratitude for this book.”

—Yiyun Li

“With An Unnecessary Woman, Rabih Alameddine has accomplished something astonishing: a novel that is at once expansive and intimate, quiet and full of feeling. Aaliya is one of the more memorable characters in contemporary fiction, and every page of this extraordinary novel demands to be savored and re-read.”—Daniel Alarcón

“An Unnecessary Woman offers a testament to the saving virtue of literature and an unforgettable protagonist . . . . Alameddine maintains a steady electric current between past and present, fantasy and reality.”—D Repubblica (Italy)

“A contemporary fable about passion: passion for literature and the passions of love.”—L’Unita (Italy)

“Passion is the key to this book, which has already been hailed as a masterpiece: passion for a man, and passion for books.”—Oggi (Italy)

About the Author

Rabih Alameddine is the author of the novels Koolaids, I, the Divine, and The Hakawati, and the story collection The Perv.

The New York Review of Books

Escaping Beirut

Robyn Creswell

In a splendidly vituperative passage in the Lebanese writer Rabih Alameddine’s first novel Koolaids (1998), one character says:

I fucking hate the Lebanese. I hate them. They are so fucked up. They think they are so great, and for what reason? Has there been a single artist of note? A scientist, an athlete? They are so proud of [Lebanese novelist Khalil] Gibran. Probably the most overrated writer in history. I don’t think any Lebanese has ever read him. If they had, they would keep their mouth fucking shut.…The happiest day in my life was when I got my American citizenship and was able to tear up my Lebanese passport. That was great. Then I got to hate Americans.…I tried so hard to rid myself of anything Lebanese. I hate everything Lebanese. But I never could. It seeps through my entire being. The harder I tried, the more it showed up in the unlikeliest of places. But I never gave up.

Many of the funniest moments in Alameddine’s work—and he is essentially a comic writer—revolve around the difficulties of trying to escape the past. The heroes of his fiction are all misfits of one sort or another. They rebel against what they take to be the tyrannical conventions of Lebanese society—its patriarchy, its sexual norms, its sectarianism. In most of his novels this revolt takes the form of flight to America, what one character calls an escape “from the land of conformism to the land of individualism.” (Alameddine is from a prominent Lebanese Druze family and has lived much of his life in San Francisco.) Looming behind these singular stories is the larger history of dislocation caused by the civil war, when many Lebanese—the ones who could—left. In America, Alameddine’s characters discover that the pleasures of individualism often turn out to be empty, and their host country’s foreign policy, particularly its support for Israel, is a constant irritant. So their emigration is only ever partial; the old world haunts all their attempts at reinvention.

In Alameddine’s new novel, An Unnecessary Woman, the narrator, Aaliya Saleh, is a septuagenarian literary translator who has stayed in Beirut—“the Elizabeth Taylor of cities,” as she calls it, “insane, beautiful, tacky, falling apart.” But Aaliya does not feel at home in her native city. For most of the novel, she walks through her neighborhood in West Beirut, remembering how it used to be, before “the virulent cancer we call concrete spread throughout the capital, devouring every living surface.” She recalls past lovers and favorite books, as well as the bitterness of her family life. In Aaliya’s case, estrangement from her relatives and from the city she lives in has led to an internal emigration. “I slipped into art to escape life,” she tells us. “I sneaked off into literature.” When not wandering Beirut’s streets, she remains in her apartment, communing with tutelary spirits—every New Year, she lights two candles for Walter Benjamin. In her old age she has become more and more devoted to her art and the pleasures of her own mind, a latter-day version of modernist mandarins from Valéry’s Monsieur Teste to Canetti’s Professor Kien. Aaliya’s name, as she likes to remind us, means “above,” or “the one on high.”

Aaliya is a childless divorcee in a country where social life revolves around the family. But the deeper source of alienation is her “blind lust for the written word.” Her day job is at an independent bookstore with no clientele. And as a translator, Aaliya is not just a reader, but a reader in extremis. Her tastes run to what we now call “world literature”: W.G. Sebald, José Saramago, Javier Marías, and Danilo Kiš (she works from the French or English versions). This is a lonely passion. “Literature in the Arab world, in and of itself, isn’t sought after,” she informs us. “Literature in translation? Translation of a translation? Why bother.” Aaliya has translated thirty-seven books into Arabic; none have been published. She’s never bothered to try.

Aaliya is not a very convincing translator. With no hope of publishing her work, she claims to be driven only by her esteem for the great writers and the joy she takes in the activity itself. This is already a little sentimental, but her description of her work is simply implausible:

My translating is a Wagner opera. The narrative sets up, the tension builds, the music ebbs and flows, the strings, the horns, more tension, a suddenly a moment of pure pleasure. Gabriel blows his golden trumpet, ambrosial fragrance fills the air sublime, and gods descend from Olympus to dance—most heavenly this peak of ecstasy.

Whatever she’s doing, it isn’t translating. Not because the job is joyless, but because its satisfactions come from the experience of obstacles faced and overcome, or skillfully finessed. In Aaliya’s account, it is one moment of bliss after another. This is typical of her relation to literature in general. An Unnecessary Woman is a kind of commonplace book, stuffed with citations from Aaliya’s favorite novels and poems. Everything that happens to her provokes a literary reminiscence: an unwelcome neighbor makes her think of Sartre (“Hell is other people”), which makes her think of Vallejo (“the torment of Hell is noise”); feeling lonely makes her think of Camus (“the weight of days is dreadful”); Beiruti garbage collectors are so many Sisyphuses. We get it: this lady has read a lot of books. But in fact Aaliya is less a devotee of literature than a gourmand. She “salivates” over the “beautiful sentences” of Claudio Magris; Marguerite Yourcenar’s versions of Cavafy are “like champagne.” (Constance Garnett’s translations of Dostoyevsky, on the other hand, are “milky tea.”) Reading a good book for the first time is “as sumptuous as the first sip of orange juice that breaks the fast in Ramadan.” And it isn’t just literature: “When I first heard Wagner, Messiaen, or Ligeti, the noise was unbearable, but like a child with her first sip of wine, I recognized something that I could love with practice.”

Most of the time, however, Aaliya’s devotion to literature is taken seriously. Her passion for translation is the prime source of the novel’s claim on its readers’ sympathies. The loneliness of this passion—and therefore the strength of our sympathies—is heightened by the idea, which Alameddine insists on, that Aaliya is pursuing her vocation in a cultural desert. “I understood from the beginning that what I do isn’t publishable. There’s never been a market for it, and I doubt there ever will be.” In the same spirit, when Aaliya steals some titles from the bookstore where she works, she is doing a public service:

Had I not ordered some of these books, they would never have landed on Lebanese soil. For crying out loud, do you think anyone else in Lebanon has a copy of Djuna Barnes’s *Nightwood*? And I am picking just one book off the top of my head. Lampedusa’s *The Leopard*? I don’t think anyone else in this country has a book by Novalis.

In passages like this, Aaliya becomes a more problematic narrator than Alameddine seems to intend. She is soliciting our sympathies—the sympathies of non-Lebanese readers, who are clearly the novel’s intended audience—by flattering our prejudices. For in reality, Beirut is no literary desert. It is the publishing hub of the Middle East and has been for a long time. Bookishness is central to Lebanon’s self-conception, as the response to the recent burning of a bookstore in Tripoli attests. Nor is it hostile to literary translation. To the contrary. In the late Fifties and Sixties, when Aaliya would have been in her mid-twenties, Beirut was home to the best literary magazines in Arabic, which were full of translated fiction and verse. Perhaps the most influential of these journals was Shi‘r (Poetry), a modernist quarterly modeled on Harriet Monroe’s little magazine of the same name. Between 1957 and 1964, Shi‘r published translations of Walt Whitman, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Paul Valéry, Saint-John Perse, Antonin Artaud, Henri Michaux, Yves Bonnefoy, Federico García Lorca, Octavio Paz, Salvatore Quasimodo, Rainer Maria Rilke, and many others. The magazine’s chief critic was Khalida Said, wife of the Syrio-Lebanese poet Adonis. Other journals during the same period translated leftist intellectuals such as Sartre, Nâzım Hikmet, Paul Éluard, Pablo Neruda, and Louis Aragon. Somebody may even have had a copy of Lampedusa.

Is it conceivable Aaliya would have no knowledge of this history? She tells us she started translating at the age of twenty-two, in 1959, just as the Beiruti rage for translation was in full swing. Most literary magazines were published in Hamra, Aaliya’s own West Beirut neighborhood. And they were published by her kind of people—cosmopolitan misfits, some of whom, like the poets and critics of Shi‘r, argued for a version of artistic autonomy that mirrors Aaliya’s own. Maybe it is conceivable she would know nothing of all this; maybe Aaliya is simply a recluse whose greatest pleasure happens to come from translating literary fiction. Maybe, but then her rhetorical question about Nightwood sounds less like a cry of anguish than ignorant snobbery. And the thirty-seven moldering manuscripts, whose fate turns out to be central to the plot, seem less like a rare and precious archive than a monumental quirk.

Alameddine’s own relation to the Lebanese literary history is similarly fraught. He belongs, and yet he does not want to. Alameddine’s recurring focus on the experience of emigration, the opportunities of self-creation offered by leaving home, his interest in questions of language and identity, and his mixing of Arab and European forms—all this places him squarely within the Levantine tradition of mahjar literature (mahjar is Arabic for “the place of emigration”). This is a tradition that begins in the late nineteenth century and includes contemporary writers such as the novelist Rawi Hage and the playwright Wajdi Mouawad. The best-known and by far the best-selling member of this group is Gibran, though in the United States he tends to be viewed as a New Age parabolist of indeterminate origin rather than as a specifically Arab writer. Alameddine, of course, wants nothing to do with this inheritance—for him, Gibran is “the most overrated writer in history”—and his way of telling stories stages its own kind of revolt.

Each of Alameddine’s first three novels upsets realist conventions in its own way. Koolaids flits back and forth between wartime Beirut and San Francisco during the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s; it is a montage of voices and stories, a form Alameddine credits to Jean Said Makdisi’s memoir, Beirut Fragments (1990), though Elias Khoury’s pioneering novel of the civil war, The Little Mountain (1977), is probably the ultimate source for this technique. Alameddine’s second novel, I, the Devine (2001), is narrated by a Beiruti Druze woman who struggles to maintain stable relationships after emigrating to the US; it is told in the form of first chapters—the narrator keeps trying and failing and trying again to write her memoir. In The Hakawati, (2008), Alameddine borrows from the fabulist Arabic oral tradition to construct an interlocking series of tales framed by the story of a Lebanese man who returns from Los Angeles to keep vigil at his father’s deathbed. One motive for this style of storytelling may be the fractured state of Lebanon, whose social landscape often seems to lack any common ground. “What if I told you that life has no unity?” says a character in Koolaids. “It is a series of nonlinear vignettes leading nowhere.” But it is also a way to resist, without entirely foregoing, the realist commonplaces of class, religion, and locality. Alameddine doesn’t want his characters to be defined by their sectarian identities any more than they do. It is this tussle between the claims of home and the attractions of flight that run through his fiction.

This is nicely suggested in a vignette from Koolaids. One of the book’s protagonists is a Lebanese abstract painter living in San Francisco (Alameddine was a successful painter before he turned to writing). A countryman is shown one of the canvases, which consists of irregular yellow rectangles, and becomes puzzled when a salesmen calls it abstract art. “But they are the sides of our houses,” the Lebanese man says. “That’s how the stones look back home. Exactly that yellow color.” The painter wants to escape into the purity of form but his content remains stubbornly local. Likewise, in I, the Divine the expatriate narrator speaks for many characters when she complains to a friend,

Here I am, the black sheep of the family, yet I’m still part of it. I tried separating from the family all my life, only to find out it’s not possible, not in my family. So I become the black sheep without any of the advantages of being one.

You can never go home, but you can’t entirely leave it, either.

An Unnecessary Woman marks a departure from the style and themes of this earlier work. The story is told from a single point of view and, aside from a few flashbacks, it proceeds in straightforward fashion. And yet Aaliya is no more at ease in in Beirut than the characters who actually leave. This may reflect a common feeling among Beirutis that the city rebuilt after the civil war is a bewilderingly different place from the pre-war version. But it also comes from Aaliya’s sense that Lebanon is a deeply parochial country, which she can only escape by reading Sebald and Saramago. “Literature is my sandbox,” Aaliya explains early in the novel. “In it I play, build my forts and castles, spend glorious time. It is the world outside that box that gives me trouble.”

The most convincing passages in Alameddine’s novels, however, are not his paeans to literature but those moments when he represents his characters at their worst. Koolaids includes a playlet featuring two upper-class Lebanese women meeting in a café in Paris to gossip about their friends: “The Ballan girl is incredibly ugly. I can’t imagine what [her husband] saw in her.” “As ugly as the Bandoura girl?” “No, my dear, that one is really ugly. This one is close, though.” “That one was so ugly. I couldn’t believe she found a husband.” “Money, dear, money. Daddy has money.” This goes on for ten pages; the whole thing is wicked and pitch-perfect.

Another memorable episode occurs forty pages into An Unnecessary Woman. Aaliya tells the story of Ahmad, a bookish young Palestinian who once helped her at the store and sought her reading recommendations. As soon as the war starts, he joins a militia and quickly rises through the ranks. Rumors suggest he has become an expert torturer. Now Aaliya wants him to get her a gun. Her apartment was burgled—the city is slipping into anarchy—and she needs it for self-defense. She meets Ahmad at his well-appointed apartment and finds a very different man from the one who helped her stock the shelves: “Slacks pressed and tailored, the white shirt fitted and expensive, the face smiling and clean-shaven.” Aaliya, on the other hand, hasn’t showered in many days—running water has become a luxury—and wears a pink tracksuit with sequined swirls. Ahmad says he will give her a gun (and a hot shower) in return for sex. She agrees.

During intercourse, on her hands and knees, Aaliya feels Ahmad’s fingers squeezing spots on her lower back and suddenly realizes that he is removing her blackheads. He apologizes, “It had been unconscious. He couldn’t see a blackhead on his own skin without removing it and didn’t realize he was doing the same with me. I asked him not to stop.” Here is moral capitulation, erotic pleasure, vanity, and surprising tenderness—fiction that matches the complexity of history. All the rest is literature.

Rabih Alameddine’s An Unnecessary Woman is published by Grove Press.